Episode Guest

Brian Schwieger, Chief of Interpretation at Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site

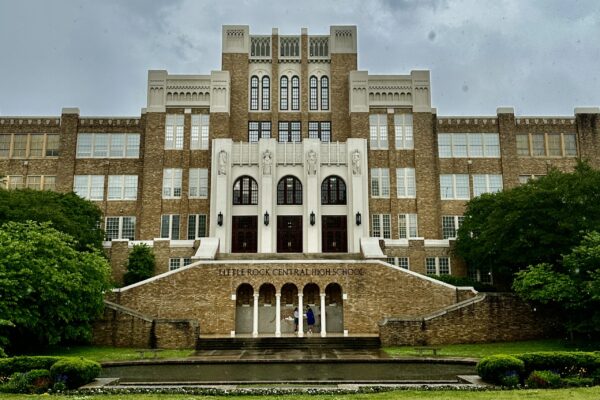

Park Stats

Location: Little Rock, Arkansas

Park established: November 6, 1998

President in office: Bill Clinton

Park size: 28 Acres

Visitors: 92,108 in 2022

Fun fact: It is the only National Park Sight unit with a functioning high school as its focal point

Park Conversation

So tell me a little bit about the park, why it was created back in 1998 and its significance in the park system.

I think that central high school and national historic site would exist today had it not been for President Bill Clinton, who is an Arkansan. But I think that his being in office 25 years ago this November, expedited the inclusion of this within the National Park system.

If you look within the National Parks landscape, there are many places that are like Little Rock Central High School. Down the road from us, you’ve got Selma to Montgomery National Historical Trail. You’ve got Tuskegee, Manzanar in California, there are parks that are culturally resourced based and talk about stories that are so interwoven in the fabric of America.

The National Park Service has made a concerted effort to protect places like this and to protect stories, to have interpretation and education around these very important universal concepts and themes that are not just American, they cross every border, and they speak every language. It’s great that this place was made into a National Park site 25 years ago.

From 1957, for about 30 years, other than people who experienced it what happened in Little Rock wasn’t addressed. There wasn’t an owning up to or admission. I know the Little Rock Nine have said that it’s not something talked about, not out of shame, but out of trauma.

In 1987, the governor of Arkansas, had the Little Rock Nine back to the governor’s mansion to be in the place where the plot was conceived to deny their entry into the school. That governor was Bill Clinton. I think the seed was planted in his mind, from an early age. First in Hope and then in Hot Springs as he, like many, watched this story unfold on television. And he felt a connection to the nine. So when he is in this position of authority to recognize and to shine a light on the heroes of this story, to invite them back, I think was no small, acknowledgement of their importance.

From that moment until 1997, the 40th anniversary, there begins a smaller groundswell here in Little Rock, about turning something into a place like a museum, a place of memory of recognition, a place where visitors can come and have an interactive, meaningful, inspirational experience.

Some people here in Little Rock, local leaders, business leaders, people in the community who felt passionately that this story needed a place like this. We were able to acquire the Magnolia Mobile gas station with the help with the city of Little Rock. That eventually became the first museum. In 1997 it becomes the first visitor center for this National Park site, a building that had been neglected in prior years, but was so important during the moments of the crisis because of its payphones, of something that’s even kind of an antiquated device today. The media’s coverage of this could not have been as, widespread without payphones. That mobile station becoming a visitor center, having an exhibit that interpreted the story, then being handed over.

With greater means and greater opportunities to the National Park Service, and the creation of a National Park site under President Clinton, it’s a great moment because it introduces a story to people who used to think of National Park sites as these big outdoor open spaces, and now they realize that you can’t tell the story of America without Independence Hall. You can’t tell it without the MLK Memorial, and you can’t tell it without a place like Central High School, just like you couldn’t without, Big Bend or Yellowstone. And these places are America, whether good or bad, whether casting America in a positive light or some of its darker moments, like Little Rock was, you have to protect these places for everyone.

And at the heart of this story is this fight for education, this attempt at equal protection with the 14th Amendment guaranteed. And it’s great that this agency, the National Park Service, has just continued in recent years. One of the more recent additions is the home of Myrlie and Medgar Evers in Jackson, Mississippi. And the story there of that incredible family that still continues with the Evers Foundation and their children. These are stories that, even though they happen in a specific place and time and moment, they are timeless and they are just as important.

Little Rock is just as important 65 years after, as it was when it happened.

These are the things we need to include. We need to have open to everyone. We need to provide access, provide programming so that the connection knows no bounds.

I’d like to go back a little bit to explain to the listeners Little Rock and the High School. It was after Brown v Board of Education’s Supreme Court ruling, the decision that “separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” The actions here in Little Rock were the spark for desegregating schools certainly, but also a sport for everything in the integration movement in the United States.

Brown happens May of ‘54. Little Rock happens September of ‘57. In that interim, you see some compliance across the country.

I think so much of the civil rights movement we think happens in the South, which is not true. Much of the resistance to integration doesn’t happen in the South. But there is, especially in this part of the country, it’s called massive resistance. It’s the, you know, putting the foot down. It’s signing something called the Southern manifesto, which is this promise in ‘56 by essentially all of the southern congressional delegations to not honor Brown. To make education a state issue and not see compliance as federally mandated.

Brown kind of, lays out the foundation for, you must do this. There’s a second Brown decision in 1955 that says you must begin integration with all deliberate speed. Because many places move really slow, and they don’t have a timeline for how to comply with this.

Little Rock’s not the first school to integrate. It’s not the first school in Arkansas to integrate. But it’s this flashpoint when all eyes, think about it, television is in more homes than it’s ever been at this point, post-War War II. So, you’ve got a lot of captive audiences watching Little Rock. You’ve got, unfortunately, the perfect politician in place here in Orville Faubus. His aspirations are probably to be where President Eisenhower is. He sees this moment as a turning point in his career. He wants to be elected to a third term in 1958. And so, he makes this political bargain with a rival that forces him to do what he does.

And it’s the first of the, what we’ll call the upper south capital cities, to integrate schools. Think about the eyeballs in Montgomery, Alabama, or Jackson, Mississippi, or Baton Rouge or Atlanta that are watching what precedent is going to be set in Little Rock for places that haven’t complied with with the law yet. You get all the ingredients for that recipe all at the same time.

It forms this volcanic explosion that involves the President. It involves two different sets of military forces – one state and one federal, the Screaming Eagles. Everything comes together at this place and involves nine 14-, 15-, and 16-year-old students.

It’s an incredible story.

We just did a program earlier and we read part of my history book from graduate school here in Arkansas. When you read this in history books, it keys in on Eisenhower and Faubus, the 101st Airborne and the National Guard.

In history, sometimes it’s like we talk about hero vs. villain, compare and contrast. In nearly every book it briefly mentions the Little Rock Nine. It might say nine children, maybe like children’s, a pejorative, right? How much could they know their children?

These were not nine naïve young people. They had been told about this. Now they had no idea what they were going to face, but no one did. But they were brave beyond any explanation. They were courageous. Their integrity and their commitment to non-violence.

I want this opportunity. I want a better education to the extent that you’ll have to take it from my hands. I’m not going to hand it to you. It cannot be understated, but in so many cases in history books, it’s completely left out.

I think it’s important to respect them for what they did. Can we say all nine names?

Yes, for sure. You had one senior that year, Ernest Green, the only graduate of the year of integration. He graduates in May of 1958.

You’ve got three 10th graders, Jefferson Thomas, and Gloria Ray Karlmark, she’ll graduate the following year but was in 10th grade for this portion. Carlotta Walls LaNier or Carlotta Walls then. And Carlotta and Jeff will graduate in 1960, but there’s a gap year.

And in that gap year, those juniors who we will mention, don’t even get to finish school at Little Rock Central High School because the governor closes the high schools in Little Rock. But you’ve got Elizabeth Eckford and Minnijean Brown Trickey, who is expelled from Central High School and finishes in New York. Melba Pattillo, Terrence Roberts, Thelma Mothershed.

The lost year is another portion of the story that hardly outside of Little Rock or maybe Arkansas, doesn’t get taught a lot. The recourse of integration, the change that happens in the immediate attempt by the governor to just kind of regain ground lost for his own political gain and maybe just to save face. Eisenhower kind of made him blink and now it’s, I’ve got to do something to get my base back.

It’s one of those where “Heads, I win. Tales I win” because the public votes on it. In Little Rock, there was a special election in the fall of 1958, and when the military leaves end of May, it’s a whole different landscape here in Little Rock.

Much of the attention has already subsided nationally from what’s happening here. Once the military gets them in, in September of ‘57, the governor sees this window and holds a special session of the Arkansas legislature and these segregation laws get passed and put on the books leading to a special election. And the “heads I win tails I win” is this, if you vote yes, Little Rock, you are in favor of full racial integration of all schools in the district. Not just the other three high schools, but every other school, elementary and middle. If you vote no, you’re against it, then the argument is, we’ll just stop it in the only place where it’s happened.

It’s only happened in Little Rock at Central High School, and while his logic is ethically incorrect, it’s not flawed if you look at the precedent. We only could have integration in Little Rock with a military presence. And now in the absence of the military, how can we continue it? It’s mutually exclusive.

So, by a three-to-one margin, the no says we don’t want our child to experience what just happened across the street at Central High School. The governor closes Central, but for good measure, he closes the other three high schools as well. 3,600+ high school students, including those remaining seven – minus the graduate, minus Minnijean who can’t come back to the school district – now have to find in-person education.

It’s a really interesting scramble for some. But if you’re a white student, you just have myriad options. You can go to North Little Rock. You can go to a school district here locally where the commute’s not that bad. You can go to a private school. Private schools seem to spring up almost overnight in and around Little Rock to serve those students.

There was a school that was open for one year only, and it was called TJ Rainey. They were called the Rebels, as a nod to this story. We have their yearbook, the yearbook from that one year during the lost year. If you open the front cover full page, it’s Governor Faubus. The governor tries to open a private school inside Central High School until another judge stops it. And the victims that year, families, businesses, but it’s those students. It’s the Little Rock seven who remain. It’s other minority students, or other students who don’t have the means to commute or go live in hot springs, go to school during the week, and come back on weekends.

Three-quarters of the white student population in high school that year, they find a school to go to. Only one-fourth of the African American students do. With that shock to the educational system, when schools reopen after only a year, it’s slowly coming back to the norm. If nine was the norm, there were only five students of color when schools reopened. Many face the blame like they had closed the schools the year before.

In the absence of the military, there’s still violence and they are completely ostracized. If you’re Jefferson and Carlotta, think about their experience. The first year it’s this famous year. It’s the year of the military. Year two it’s at home without Zoom or Google Classroom like kids would have today. And then year three, when you come back, there’s no military presence.

Carlotta’s house gets blown up in the spring of her senior year. It’s just an awful experience and the governor’s fingerprints are all over this.

He is reelected again and again, then leaves office by his own choosing. After 12 years in office, he’s Arkansas’s longest-serving governor, and will always be now because of term limits. After an unsuccessful rise, he tries to run again in the 1980s. He wants to come back and be governor again and can’t get through the primary in Arkansas because of Bill Clinton. Clinton stops him and Clinton signs this into law. I don’t know if that’s the correct use of the word irony. But it’s interesting that his path is blocked again.

And the creation of this place that talks about the true heroes of the story is signed into law by former governor, then President Clinton.

Besides the beautiful storytelling of the Little Rock Nine, one of the things that was surprising to me as I went through the Visitor Center and the exhibit is seeing the impact that the Little Rock Nine have had on movements, human rights movements, since then.

I think one of my favorite moments I’ve ever had personally or professionally was because of this place this was one of those just serendipitous occasions, Minnijean Brown-Trickey’s daughter, Spirit, was the Chief of Interpretation here. Minnijean would often come into the building to see her daughter.

On one occasion, there was a group of young ladies from Afghanistan who were the first young women in their family to ever go to school.

This was after Americans had become aware of someone like Malala Yousafzai and what she had gone through and what the Taliban had done trying to stop her opportunity of education. A different time, different place, yet the same kind of intent. These young ladies were in our classroom, and we were talking with them about this story and the extent to which I they knew the story was incredible.

They knew the ins and the outs of this said that the inspiration they drew from this story was immeasurable. I was with them and excused myself. I went and told Minnijean, one of the nine, who was in that room and said, “can I just bar you for a second?” She was so excited to meet these young ladies.

When I took her in the room and I introduced her the look on their faces was of just wonderment and excitement, but also knowledge. They, knew her story. One of those young ladies said, “You are our hero.” Without missing a beat, Minnijean said, “No, you are mine.”

To watch that generational difference, there was no difference. Here is Minnijean, years after this moment, but still advocating for the rights that these young ladies, half a world away, had just reached out and grabbed for themselves and to know that link from Little Rock, Arkansas reached Afghanistan.

To know that story tied, any kind of difference – generational, language, age, anything – solidified for me how important this story is. It’s been life changing to meet people from everywhere who know the story and have been moved by it.

I helped young lady in England. She researched and wrote and presented about the Little Rock Nine. And this story, it’s timeless. I think it speaks so well to young people because it’s a story about young people in an era, in an age when maybe role models are fewer and farther between, it’s great that these have never left and hopefully never leave the public consciousness.

I’m constantly reinvigorated when we talk about this story and see the reaction and see the emotion and see the connection on the faces of the people that we are lucky enough to get to serve here at this place. It’s a testament to the Little Rock Nine.

There’s a quote on the wall by cultural anthropologist, Margaret Mead, and says,

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

Learning and hearing about the Little Rock Nine, and what they were able to do, is just a spark for the rest of the world.

That’s the wonderful part about our modern, civil rights movement. While a lot of the stories that we know or we are taught are adult led, they’re youth driven. You look at the Freedom Writers, you look at sit-ins, you look at Woolworth counters, you look at Freedom Summer, all these things, even the Children’s March, those are children younger than the Little Rock Nine.

All these things look at what young people can do, and I think that there’s no coincidence that here at Ernest Green’s graduation, the first of the nine to graduate, is Martin Luther King. And maybe that seed planted in a not even 30-year-old man’s mind and look at what young people can do. I think that’s why young people take motivation from Central High School & the Little Rock Nine. They see a 14- and 15- and 16-year old students, like the Nine would’ve been. If they can do it, there’s no reason why I can’t.

Every excuse has been taken. You don’t need to be an adult. You don’t need to be 18, you don’t need to be able to vote. Those things may help, but you don’t have to have those accomplishments or those credentials to do something great. You must have the courage and integrity to do it.

Little Rock is part of the National Park Service but is a Historic Site. Can you explain the difference?

The differences in the designations, or the nomenclature, of a National Park to a National Historic Site, or to a National River, or a National Lake Shore, or a National Monument. We all have the same mission agency-wide, but we have different last names. A place like Hot Springs National Park, or Big Bend National Park, a national park is usually a larger place, an outdoor place that’s got larger natural features to it. You think about the Smoky Mountains or Grand Canyon or Yellowstone or Yosemite. These national parks were set aside in the infancy of this agency to protect these wild and wide open spaces.

Over the last hundred and seven years that this agency has been in existence, the focus remained on those same values of wilderness and open spaces. And it’s begun to focus on places like this or places that are smaller in size, but by no means smaller in scope of what they protect.

Places like Central High School, and National Historic Site are more about a cultural resource and less a natural resource, like, the thermal water down the road in Hot Springs. These are places that are still so very important to be protected.

The designation, I think just helps the visitor understand in planning what the focus is going to be. If I’m going to go to a National River, it can be expected that there might be some outdoor aquatic activities that I can canoe or float or kayak. If I’m going to go to a National Monument, maybe then that’s something that’s focusing on commemorating and honoring an individual or a place or a movement. If I go to, a National Trail there’s probably some hiking involved or tracing history through a trail like the Trail of Tears or Selma to Montgomery.

I think the designation, our name may be National Park, et cetera, probably helps better the visitor in understanding ahead of time what to expect. But I don’t think by any means, you should think if something is not a last name, National Park then why is it part of this National Park Service?

There are 420 plus units and not all of them have the designation of National Park, but they’re no less important.

One of my tips when planning a trip to a park is to determine what you want out of it. And I think the first stop in any park is at the Visitor Center. The Rangers always have great suggestions on what to do in that park, and they have bathrooms.

I would say when you’re planning, always go to the National Park Service website or to that park’s website. We get a lot of visitors who will use search engines and they bring their understanding or their planning. Use the official National Park Service website. Go to nps.gov and make that the jumping-off point.

If there are any kind of alerts, whether it’s construction or weather, or a special event or a closure, look at park calendars to see what events might be happening when you’re planning on coming or if you want to plan around a special event.

The website dropdown menu has a “Plan your visit” section.

If you’ve got half a day, you’ve got a full day, we want to help you put together a reasonable agenda that will be enjoyable. Sometimes, in an attempt to see everything, you see nothing. We want to make sure you have a meaningful visit.

And then use the NPS app. We even have a 45-minute narrated with a transcript audio tour that Central High School students recorded it for us.

At Central High School, you can make an appointment visit, but you could also use it as a pit stop on a road trip. It’s very digestible. In the visitor center, you have the main ranger station, and then you have the exhibit.

The visitor center encapsulates the exhibits and all the amenities that people are used to. You mentioned restrooms and water fountains and a bookstore.

In that bookstore, you can purchase things about this story and gifts. The exhibit has a film and things to watch, touchscreen or audio stations, and tactile ways to connect. We have devices that have assistive listening and captions and audio description so they can be engaged with by persons with disabilities

You have this wall of windows with phones that you can pick up and hear different stories from those days. While you listen, you are looking out at the mobile station and high school. They show original footage while you are looking out on the street today.

There are places like Central High School and many other places that are protected by the National Park Services that we call a “Power of Place” place. When you can be here and stand in that spot, you can look and listen and hear and engage all of your senses and all of those emotions.

There’s no better place to connect to a story or to learn or to connect with that resource than to do it in the place where it happened.

We’re really fortunate that a recent boundary expansion now includes the seven houses across the street from Central High School. And while we don’t own them, they have some level of protection. So, when you step out onto, what is now called Little Rock Nine Way, the street in front of Central High School, you don’t have to imagine where’s the gas station, where are the homes where people lived. Where’s the school?

It’s the same scene. Go stand on the grounds of Central High School. Go stand and just look at that place and think about, and imagine yourself, if you’re one of those nine students, how do you walk in those doors on day one, day two, day three, without giving up, without fighting back?

I think it will bring you to an emotion that hopefully will be stirred within you.

The first stop is the Visitor Center. Then you can walk around. There’s a beautiful commemorative garden. Then walk down the street to the high school and memorial bench.

I found it interesting that depending on where you are personally, the experience changes. I found it to be reflective and meditative yesterday when I first got here, and then high school let out. And the streets and the lawn fill with kids, to see the integration. I mean, it is a diverse group and they’re playful and they’re fun. It helped me to bridge that time period, from the history I was reading about.

I was thinking about those nine kids going into the school when I was suddenly bombarded by a thousand kids coming out of school for the day. It’s incredible.

It’d be a completely different dynamic if that school were not an active high school. When you see students walk out of a place, that 65 years ago, some of those students wouldn’t have been allowed to walk in those doors.

It’s a great testament to the achievement and what the Little Rock Nine did to unlock these opportunities for students.

Speed Round

What is your earliest park memory?

I grew up in Nashville, Tennessee. National Parks were accessible to us. On vacations we’d go to the Smokies or Shiloh or Chickamauga & Chattanooga. But my earliest park memory is probably Mammoth Cave.

When you’re a little kid and you’re underground, it’s dark and it’s dirty, and you can crawl around. I loved it.

I can remember one time standing at the back of a park program at Mammoth Cave and talking to the Ranger. I bombarded her with questions because I was so curious. She was so nice and kind. I’ll never forget this.

When I became an employee with the National Park Service I called Mammoth Cave and said, “I’m sure she’s not there anymore, but can I tell you my story and what this lady meant to me as a little eight year old?” They said, well, she’s retired, but we will pass this message on. And I thought, how cool was that? The memory of my experience as a little kid, who had no concept of what I would do someday as a grownup, and how my career was formed through an experience at Mammoth Cave National Park.

What made you love the parks?

A couple things. I had a teacher in graduate school who wrote extensively about the lost year, the year schools were closed. And I think her connection to this place was so evident that when she connected me with this place to be a volunteer in graduate school, that was a seed plant.

Also, what my parents did by taking my brother and I to these places that were open and wild, like the Smokies (Great Smokey Mountain National Park), but also places of importance in our nation’s history. Civil war parks like Shiloh or Cumberland Gap. Beautiful places that have both natural and cultural significance.

I think my parents really planted this in me and then I had some really great teachers in high school who made me want to teach history. I figured out that these are some pretty unique outdoor and indoor classrooms within this agency.

I get to kind of be a teacher every day in a cool setting and get to have an impact and influence on the students we get to interact with.

Those are the people that really helped get me to this place. I didn’t get here on my own.

What is your favorite thing to do at Little Rock Central High School National Historic Site?

Just before we did this interview, we had a program with a diverse room of people. One man shared his memory of this to young people who are in college. And I love telling the story and seeing the change in people. When you start the story you watch faces change and you see people getting upset and angry and surprised and smiles. You want them to feel those things that the Little Rock Nine felt when they were living it.

So, I love seeing that range and change of emotions on a visitor’s face every day.

What park have you yet to visit but is on your bucket list and why?

You know, I mentioned Manzanar. I’d love to go to Manzanar. We just had a program that we participated in. It was a Japanese American Memorial pilgrimage. There are two concentration camps, they’re internment camps, here in Arkansas during World War II. Like Manzanar, they took the liberties away from thousands of Japanese Americans. I think just from experiencing those two camps at Jerome and Rohwer here, in Little Rock,

George Decay was here the other day. He was at Rohwer here in Arkansas, as a young man. I want to go to Manzanar and see the vastness.

What are three must-haves you pack for a park visit?

For sure you need to pack protective gear like water. And prepare, especially if you’re going to come to Little Rock, I would plan for all four seasons in one day. Plan for rain or for hot and cold. So, you know, sunscreen and umbrella, we mentioned water bottles, some snacks just have things so you can face any weather situation that you have no control over.

Number two, I would say it’s something to reflect with whether it’s your phone and the notes on your phone or a journal, you’re going to think things, you’re going to read, things you’re going to see, things that you will remember in the moment, but we don’t want you to forget for perpetuity. So, I would say bring something to write on or make sure you’ve got a way to capture those feelings.

And then honestly, my third thing, I would bring open-mindedness and curiosity. Ask questions and be open enough to let yourself be immersed in the story of wherever you are. Whether it’s a place like Central High School or a place that’s wild and wilderness.

What is your favorite campfire activity?

I love ranger talks. I love hearing somebody talk around a campfire at an amphitheater. Some of my most favorite moments or memories are those. There’s just something great about hearing somebody share a story around a campfire.

Tent or cabin?

Oh, tent. I like roughing it. I like hearing the sounds that a tent allows you to hear – the rain, the wind, the bugs.

I like to sleep on the ground.

Hiking with or without trekking poles?

You know, the older I get, I think it’s with

They’re great for balance and stability. And I’m telling you, not all terrain’s the same. You think you might have some sheer footing and you don’t want to find out pretty quickly that you don’t.

And what is your favorite trail snack?

Anything with peanut butter. Peanut butter is my go-to. Absolutely must have

in the backpack when I’m going to go out on the trail.

So I carry all three of those most of the time on my hike.

What is the best animal sighting that you’ve had?

When I worked at Guadalupe Mountains National Park, I was really fortunate I got to live in the park. Every day outside my door, I could look and see those incredible mountains.

I’ll never forget one morning I let my dog, Jojo, out. There was this pack or family of javelinas. It’s a small animal that’s like a little hog. So these javelinas. and my dog were having this stare down contest, but I think they were both figuring out what the other animal.

After about 10 seconds mama javelina came along and really loudly clicked her teeth. “Let’s roll.” And then they all kind of just trotted off.

What is your favorite sound in the parks?

You know what? It’s this, it’s silence.

Some of the places I’ve had the most transformational moments in, you could hear nothing.

What is the greatest gift that parks give to us?

I would say access because they are for everyone.

I’m going to say opportunity. Opportunity is one of the key words about our story, in no small part or no coincidence because one of the statues above the doors at Central High School has the word “opportunity” underneath it.

I think stories like this, that are protected in places like this, parks like this, give people opportunity to learn, to be transformed, to be changed, to be inspired, to be motivated. I hope everyone who visits any National Park unit takes full advantage of their opportunity to be there and just to consume as much as they can.

Read, watch, listen, talk, experience.